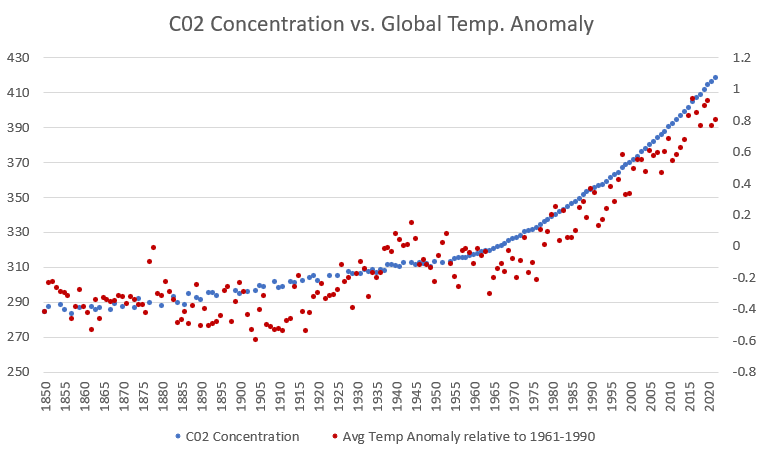

As a conservative in college (more on my background in my introductory post), and an introvert who would rarely speak up in class, I can clearly recall one moment when I did raise my hand to make a point, and it’s not a proud memory. It’s not that I got a bad response – on the contrary, I received appreciative comments from my fellow conservative classmates (I went to Texas A&M and am glad I did). But my present self wishes I’d have shut up. I don’t remember much about the lecture or who the professor was, but I do remember they showed a slide showing CO2 emissions alongside global temperature rise. I had just watched some climate-change-skeptical “documentary” which “debunked” one such chart by claiming to point out that CO2 rise lagged the temperature rise, and that this proved the rise in CO2 wasn’t the cause. So, I raised my hand and pointed this out. I don’t remember being impressed with the professor’s response at the time, but as anyone can see (chart below), I was obviously wrong. From ice core samples, we can clearly see CO2 levels were beginning to rise before 1900 and steadily continued from that point on, right in line with human industrialization. Temperature rises, on the other hand, would be a lagging effect of this initially gradual rise in greenhouse gases, and indeed we see this begins somewhere around 1930, before really taking off around 1980.

Climate change, it should be obvious by now, is happening. And as that chart of CO2 concentration shows, the correlation with economic growth powered by the burning of fossil fuels – energy sources which emit into the atmosphere CO2 which has been buried underground for millions of years – leaves little doubt as to where this CO2 came from. And indeed, scientists were predicting climate change based on their knowledge of the greenhouse effect, which greenhouse gas emissions exacerbate, before there was much evidence of it. There’s no mystery here, and the scientists who have been raising the alarm about this for decades deserve our attention. In science, the ability to predict an outcome is critical to the acceptance of a theory. The increasing pace of extreme weather – freezes, heat waves, drought, floods, hurricanes – in recent years serves as evidence that the scientists were right. No, it’s not possible to definitively blame any individual phenomenon on climate change, but as 500-year extreme weather events happen with increasing regularity, it becomes ever more unlikely that they would have happened in the absence of anthropogenic warming.

It is true that the rhetoric around climate change being an “existential threat” to humans is often overheated. Yes, the most catastrophic of possible outcomes would be devastating, but the idea that a species as adaptable as humans will die out as a result is highly unlikely. Overselling the danger probably won’t help convince those who would experience many of the hardships of an energy transition while not being on the front lines of its effects. But understanding the effects that are already here is the first step to recognizing the dangers we and the rest of Earth’s inhabitants face, and why we should see this as an urgent problem.

One of the more dramatic examples is in the arctic. The minimum extent of arctic sea ice has shrunk over 10% per decade for the last 30 years, and the sheets of ice that don’t fully melt in the summer are getting thinner. As the total amount of reflective ice shrinks, less solar radiation is bounced back into space, which means more energy gets absorbed by water or land, leading to an acceleration of melting. Furthermore, arctic permafrost is land that usually stays frozen and contains massive amounts of undecayed organic matter. As permafrost thaws, this organic matter decays and releases long-trapped carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, meaning that arctic thaw is contributing to global warming by releasing previously-trapped carbon into the atmosphere. Although it’s unclear how quickly this will happen, this is a dangerous feedback loop that we really don’t want to accelerate.

And lest we think these consequences are limited to the poles and coastal communities, one must not forget the risks of extreme weather that we’re already beginning to see. While not a new phenomenon, the increased frequency of anomalous weather events is consistent with scientific forecasts of a warming globe, and with the impacts of severe floods, fires, heat waves and droughts already proving significant to large populations around the world, it is entirely reasonable to fear how this could get worse. And we must not only worry about the impact to humans – the natural world is adaptable, yes, but is not used to adapting on such a rapid timescale. These changes are likely to lead to a loss in biodiversity and resilience on the part of animals and plants, including those we rely on for food.

The question then becomes, what do we do about it? Do we declare a climate emergency and disrupt our entire economy and destroy industries that employ hundreds of thousands of people in order to reach net-zero emissions in a decade? Or do we give up, accept that we can’t make China or India or Africa stop burning coal to fuel their developing economies, and focus on adaptation? Of course, as you might expect me to say, the answer surely lies somewhere in the middle.

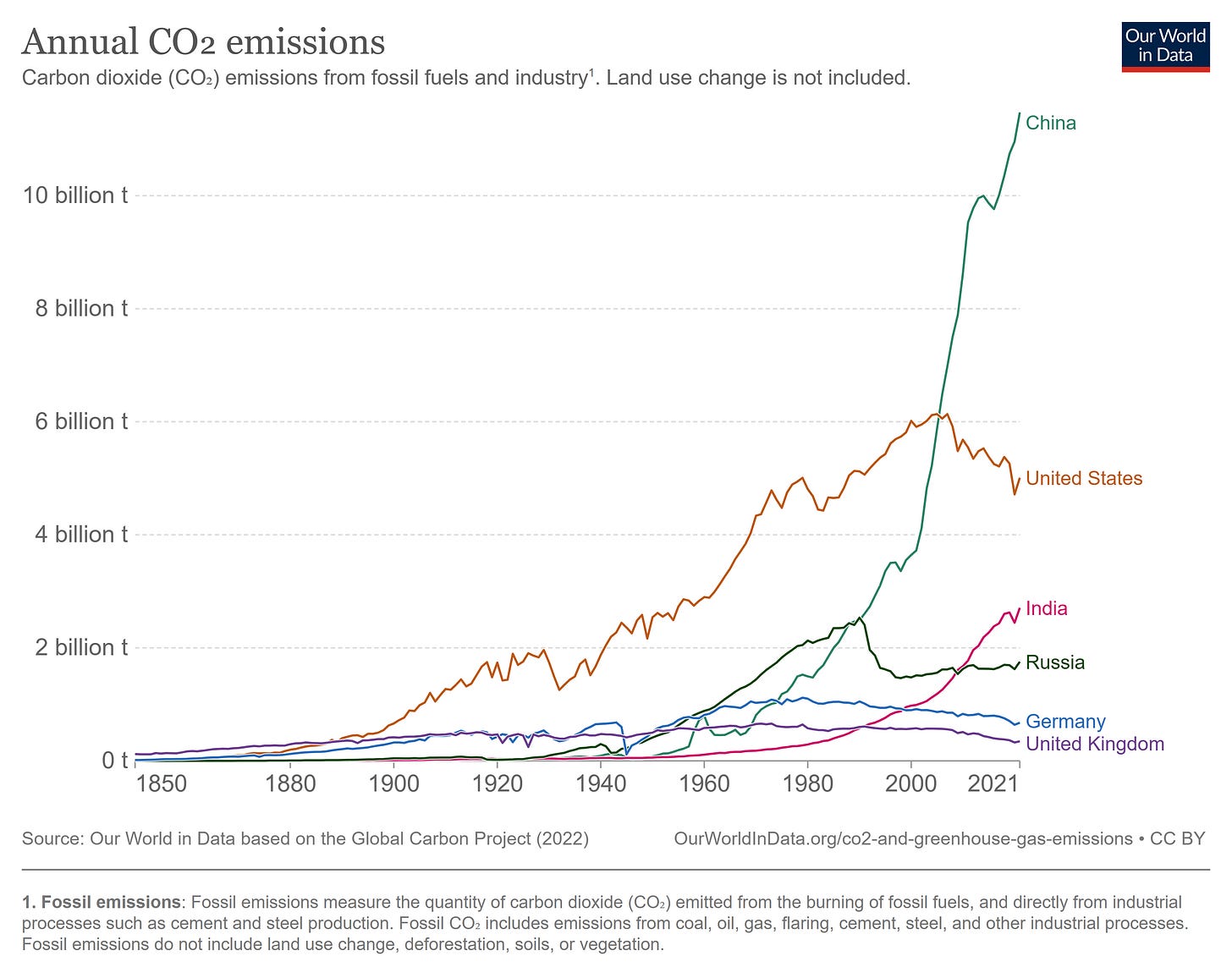

On the one hand, as the country (see chart) that benefitted most from CO2 emissions in the last century, creating disruptive externalities that are now felt by the entire globe, we have a moral obligation to take the lead by reducing our emissions. China may be contributing more to the problem now but if we consider cumulative emissions, we’re still in first place. And it may not be fair, but as an advanced economy with brilliant engineers, skilled manufacturing workers, and a strong culture of innovation, we’re positioned to benefit not only from contributing greatly to the problem, but also its solution. So, I do believe that government incentives, grants and regulations to accelerate our transition to renewable energy are justified both for the good of the planet and can be a boon to our own economic prosperity.

But it’s also worth noting that this problem is huge, complex and will take time to solve. And that argues for some moderation in our approach. Millions of Americans work in oil and gas related jobs, and even if we could quickly power all of our planes, cars and power plants without what they produce, we must have a plan for how we help those employees transition to the new economy without being left behind.

Of course, that little caveat about quickly powering our planes, cars and power plants is no small thing. Whatever you think of Elon Musk, we owe him a debt of gratitude for proving that electric cars could be viable, and cool. But even with the rest of the automakers finally entering the EV game, demand is outstripping supply. Batteries are not cheap to make at the scale needed to electrify most vehicles, and the extraction of enough raw materials is becoming a bottleneck (and is itself not exactly great for the environment). We can scale that up, and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 incentivizes more domestic production which should diversify and toughen these supply chains. But building all of that will take time.

Then there’s the issue of air travel. Planes, by virtue of the fact that they have to be hauled high into the air every time they’re used, need an energy-dense source of energy to be viable. Batteries are not there yet. Neither really is hydrogen (which can be produced using clean energy, though is rarely made this way today). Manufacturers are finding ways to improve efficiency, and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is promising, but large-scale zero-emission air travel remains an unsolved problem with a long way to go.

That suggests that carbon capture must be in the mix somewhere. True, a focus on carbon capture alone is likely to be highly inefficient and insufficient, but it’s a way to buy time while we figure out how to solve the harder problems (assuming we can power it with clean energy). But capturing carbon from the ambient air, while likely something we’ll need eventually, isn’t the best place to start because the concentration in air is relatively low. Know where we can find atmospheric CO2 in a much higher concentration? Smokestacks. So, before we go crazy on direct air capture, we should at least make sure all non-nuclear power plants are fitted with carbon capture devices. Even better is actually converting these fossil fuel plants to burn biomass (either from waste or grown in a sustainable and low-carbon way) and capturing their emissions. That’s potentially a carbon-negative power source, as it’s basically leveraging nature to turn the hard problem of direct air capture into the easier problem of concentrated smokestack carbon capture, and producing energy in the process, using existing power infrastructure. If you ask me, we should be doing everything we can to see how far and how fast we can scale this up.

And what about everyone’s favorite, nuclear? Although there are risks, and the waste needs adequate funding to safely dispose of, modern nuclear plants are very safe (see above). And zero-emission. And capable of producing immense amounts of energy, in a relatively small space, continuously. That last bit is a key point. All the solar panels and wind turbines in the world won’t meet our needs unless we have some way of dealing with their inherent intermittency. Storage is one option, of course, and there are a number of interesting options there besides the obvious answer of “battery” (and we should be looking for alternatives given the fact that we’d be competing with EVs for battery production, though Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) technology is a promising way to mitigate this by leveraging parked EVs for grid storage). But at least for the foreseeable future, we are likely to still need more conventional sources of energy to fill in the gaps in renewable production. Natural gas, as the cleaner fossil fuel and one that can be scaled up/down quite effectively to meet demand, is likely to serve this role for a while. But nuclear should not be dismissed and may indeed be the only truly clean option that can scale to meet our needs for a long time. And while I’m excited about fusion, we likely can’t wait for it to eventually become viable and economic.

There are of course plenty of other innovations that can all contribute to the solution. To dramatically reduce something as pervasive as the emission of greenhouse gases into our shared atmosphere will require a both, and approach that isn’t limited to the solutions we already know about. A carbon tax is among the most efficient policy approaches because it’s based on sound economics. Carbon emissions are an externality, or cost borne by others, that has historically been “free” to the emitter who gets all the benefits of the energy produced. This underprices carbon emissions relative to their real cost (contribution to climate change), which puts them at an unfair advantage relative to greener alternatives. A carbon tax corrects this by imposing an economic cost meant to represent the cost of those emissions. The practicalities of such a tax can be tricky (the emissions of products like fuel are easy to quantify, but others aren’t so simple), and care must be taken to get public buy-in (probably in the form of a tax credit, funded by the carbon taxes, which prevents this from imposing a net cost on most households). But there are plenty of proposals and examples of carbon taxes in other countries, so these are not unsolved problems. Carbon taxes are an unbiased way to incentivize an entire economy to reduce emissions, and I really wish it came up more often in serious policy proposals.

Lastly, we can’t forget about adaptation. We’re clearly not going to achieve net-zero tomorrow, so we must invest in infrastructure and aid to ensure coastal and vulnerable communities are able to deal with the more extreme weather we’re already beginning to see.

We have a lot of promising opportunities, and I don’t want to ignore the progress we’ve already made, thanks in large part to public-private partnerships in which government subsidies have supported nascent green technologies until they reached economies of scale that allowed them to compete on their own. But we’re a very long way from net-zero, and we won’t get there without a clear majority of society agreeing that this is even a worthy goal. Which brings us back to that experience I had in college.

That misinformed know-it-all who spoke up in that science class in college wasn’t stupid. Young, yes, and naïve. But my main problem wasn’t that I lacked the ability to understand scientific concepts or interpret data. I lacked the will to listen to viewpoints that contradicted my political views. I found an argument that aligned with my political biases and reinforced what I wanted to believe, and I accepted it as fact without much critical thinking. This is called confirmation bias, and it’s a big reason why so many Americans don’t take climate change seriously, and actively fight against common sense policies that would further our fight against it.

In my next post, I’ll address another case where confirmation bias and information silos have caused great harm: COVID.